curated by Richard Ducker

The 1960s and 1970s were a period of radical transformation in contemporary art, resulting in what Terry Atkinson has aptly described as a “complex and expanded” field of art practices and related institutions, both in the UK and abroad. The most visible legacy in Britain of such innovatory work is that now historicised under the rubric of “young British art”, with the truly innovative developments of the ‘60s and ‘70s having been to a large extent obscured by the pomp, hype and market-led fanaticism that was so much a part of the yBa’s success in the ‘80s and ‘90s. In order to carry out a critical reappraisal of this historical and political imbalance the Fieldgate Gallery, for its final exhibition at its current premises, presents the work of three important and highly influential artists who came to prominence in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s: Terry Atkinson, Stuart Brisley and Tim Head. These artists were not only key figures as artists operating within Conceptualism, Performance Art and other zones of practice, they also influenced subsequent generations of students – and not least that of the yBa – through their significance as teachers and committed commentators on art and politics, as well as upon the difficult interface between these overlapping, if only apparently contradictory fields. All three artists continue to make work today, a point that it is easy to forget or ignore in the celebrity-infested pro-youth climate so prevalent in both the art world and the broader culture. Presenting the work of these three figures at the present time (and especially in tandem) may be, in some quarters, regarded as a provocative act, or, from another perspective, perceived as one long overdue. Both interpretations are correct. Why it is important to draw attention to Atkinson, Brisley and Head at this particular historical moment is a combination of a number of elements: their work and general contribution to significant developments within fine art practice is one clutch of reasons; another is the unfortunately mannered, formulaic itineraries of much post-Conceptual art. It is surely time to reiterate that Conceptual Art and its concurrent artistic developments were critical, rigorously innovative and deeply sceptical methods of art-making, not driven by the desire for easy and insipid market-based success as is so much post-Conceptual work today.

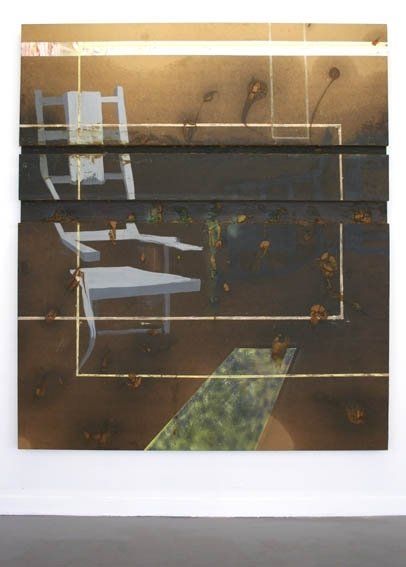

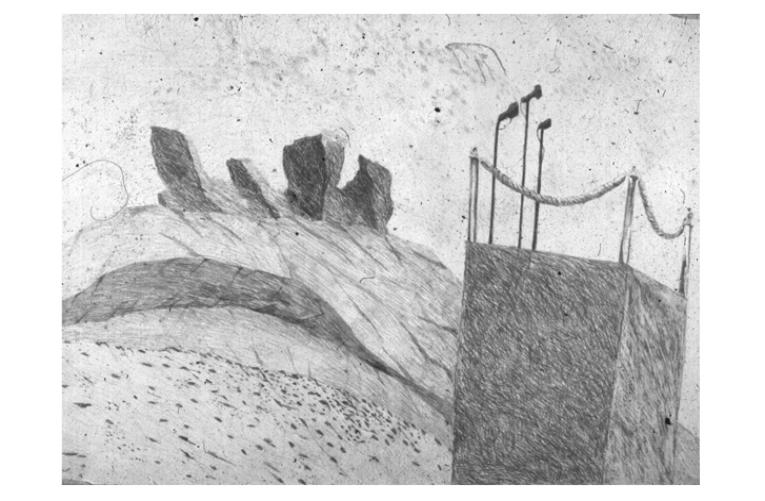

Terry Atkinson (b. 1939) has chosen to show at Fieldgate extracts from several substantial bodies of work executed in the ‘80s and ‘90s, the Irish works, the Greasers and the Mutes. Whilst the Irish pieces utilise more or less conventional painterly forms to comment upon – often in a wry and critically penetrating manner – the convoluted niceties of the political situation in Northern Ireland, the Greasers and Mutes push painting into an area that is difficult to classify as painting proper, though it is similarly hard to label it with other established terms. Employing axle grease (a substance that never fully congeals) as a substitute paint, and having squelched this viscous connotator of labour, wealth and energy into specially constructed troughs that form part of larger mixed-media structures, these constructions raise questions about what it means to expand the Modernist notion of vanguard innovation beyond its now well-documented limits. At a moment when the mass media is constantly harping on about the imminent evaporation of the Earth’s oil resources, Atkinson’s Greasers and Mutes take on a heightened relevance as allusive, impressively prescient representations of Capitalism in a state of panic and disarray.

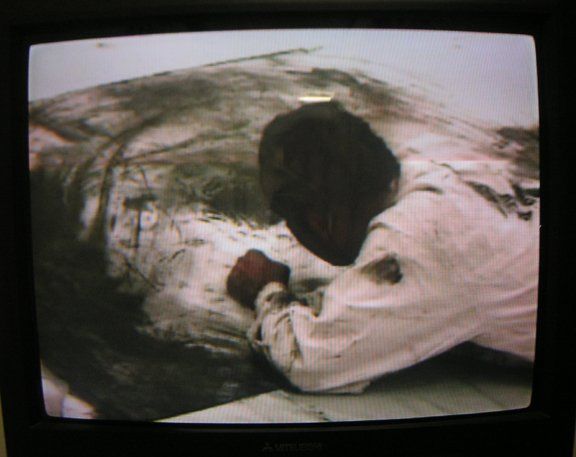

Stuart Brisley (b. 1933) has produced a highly diverse range of works and utilises a broad span of methodologies, resulting in live actions, installations, paintings, drawings and writings. His pioneering long- duration performances, first carried out in the 1960s, gained him an international reputation. Brisley’s prime contribution to this show will consist of an installation entitled “Psychocleaning” (2008), involving the deployment of various props – an old ironing board, a low plinth, a dirty white plaster leg – with other items placed in relation to these (possibly highlighted) objects. Brisley frequently works in an open-ended manner, his installations and (if he chooses to carry them out) actions developing dialogically with the space into which they are inserted or performed. “Psychocleaning” as an operative term has a number of connotations, including ethnic cleansing but also the troubled and troubling pseudo-obsession with dirt and its emphatic erasure that is so prominent a trope within Capitalism. (In 2003 Book Works published Brisley’s novel Beyond Reason: Ordure). Despite these clues or contextualising triggers “Psychocleaning” is, however, a work open to many possible interpretations; in part a potential stage-set for live action, it is also a configuration of formal and material relationships designed to act as a machine for the generation of meanings other than those consciously marked out by the artist himself.

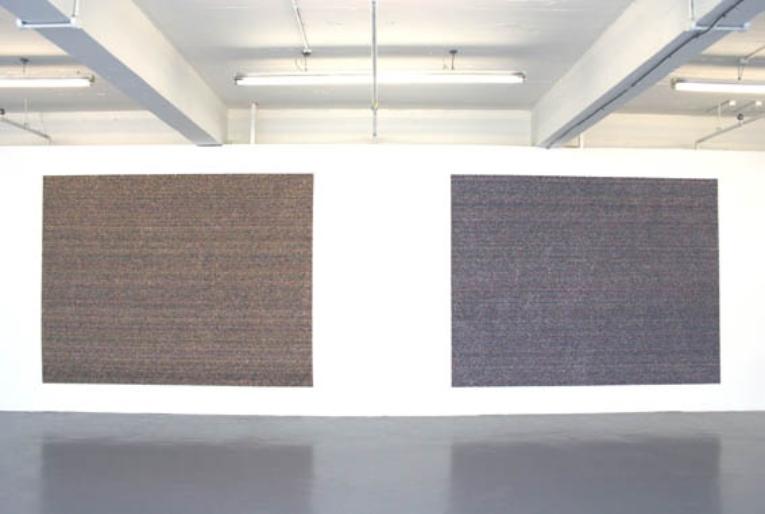

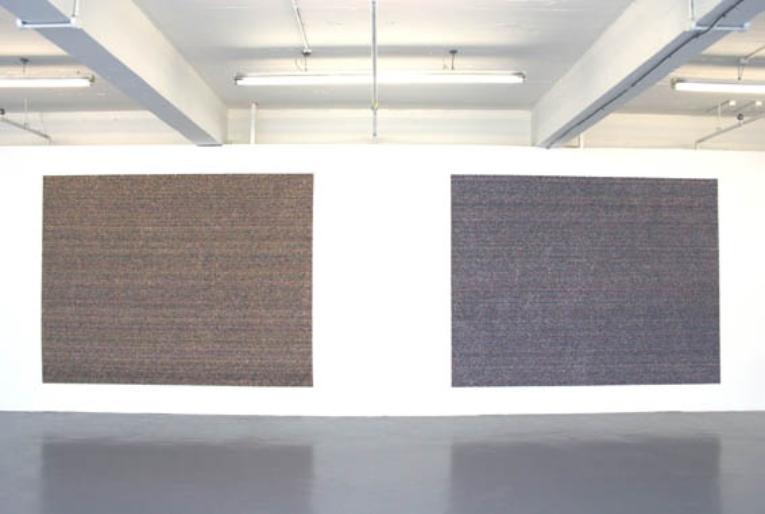

Tim Head (b. 1946) has worked in a variety of media. At Fieldgate he will exhibit a number of pieces made since 2002, concentrating upon works that take as their point of departure what he has perceptively termed the “elusive and contrary nature of the digital medium and its unsettled relationship with both ourselves and with the physical world.” Although the use of digital media is a widespread and increasingly naturalised aspect of everyday life in the West, its alleged stability and reliability is arguably somewhat overstated. Head’s recent work draws the viewer’s attention not to the coherence and practicality of the digital form but to its unreliability, its ability to generate heterogenous and diffuse results. In “Laughing Cavalier” (2002) a computer randomly selects a colour from the literally millions of possible colours held in the computer’s palette, filling all the pixels on the screen with it. This is rapidly replaced by another random colour choice in a constantly shifting process, the specific particularities of which are determined by the idiosyncrasies of the hardware being used. "Dust Flowers" (2008) are large digital inkjet prints made by vastly magnifying layers of randomly generated ink dots that reveal the latter's granular, interwoven surface.

- Peter Suchin

private view: Friday, 13 June 2008, 6-9 pm

exhibition runs from 14 June - 13 July 2008

TERRY ATKINSON

Terry Atkinson was a founding and key member of Art and Language, a group of pioneering conceptual artists founded in the late 1960's, who investigated politics and power of language and how that was open to negotiation and debate. For this group, language and images were in and of themselves political phenomena, and the same were inherent and integral to the politics of painting and expression. The group questioned the critical assumptions of mainstream art practice and criticism. Short- listed for the Turner Prize in 1985, Atkinson believes that, “through art, it is possible to further our understanding of the complex social and political world. Today, Atkinson continues to produce paintings that engage their audience both politically and critically.

[more text below]

STUART BRISLEY

Stuart Brisley, one of the most influential artists of the 60’s – 70’s, is widely regarded as the "founder" of performance art in this country, perhaps most notorious for his disturbing physical performances, examining the body politic and images of power. Brisley’s work dealt with challenging the human body in a physical, psychological and emotional manner, pushing the limits of what the body could endure, as a metaphor for the individual’s [human’ s] vulnerability. Brisley’s exploration of the essential qualities of what it means to be human by challenging the human body in physical, psychological and emotional ways. In much of his performance work, Brisley establishes a dialogue of action and reaction with his audience that pushes the boundaries of conventions of social behaviour. Archive footage of his earlier performances will also feature.

TIM HEAD

The elusive and contrary nature of the digital medium and its unsettled relationship with both ourselves and with the physical world forms the basis for the recent work. Computer programs are written to generate unique events in ‘real time’ on screens, projections and inkjet prints that focus on the intrinsic properties of these digital media. The programs operate at the primary scale of the medium’s smallest visual element (the pixel or inkjet dot) by treating each element as a separate individual entity. The medium is no longer transparent but opaque. This is an interest of Head’s that has persisted in various forms in his career which culminated in his viral digital photographs that were shown in his Whitechapel Gallery solo exhibition in 1992 and when he represented Great Britain in the Venice Biennale in 1980.

TERRY ATKINSON

The analogy which I elected to use in conceiving of the Grease Works was the hardware/software distinction of computer science.[1] I wished to make a series of works which had a software component such that the works would continue to produce themselves (or at least aspects of themselves) after they had left my (the artist’s) relations of production. An early group of Grease Works was the Warhol Chair works, where the hardboard/paint/trough construction is treated as the hardware tableau upon which the software programme (grease) is implemented and runs. Grease, being the relatively volatile material it is, continues to shift and seep according to such factors as variation in temperature, how vigorously the works may be moved one site to another, etc. Accordingly I conceived of the use of grease as the deployment of a continuing to run software programme.

Since I was assuming, for this project at least, that the given model of the artistic subject (learned and inculcated, let us say, in art school) as running (implemented) in the body of the artist (a truism in one strong sense), then, accordingly, the works of the late eighties and those made throughout the nineties, can be viewed as an attempt to increasingly focus upon making works which model, in one way or another, the artistic subject her or himself. It is clearer now (2002) that the Grease Works (the first two small Grease Works were made toward the end of 1986) were sustained attempt to make works, a component (grease) of which was a kind of automata. Grease as a kind of continuous ongoing -past-the-hand-of-the-artist moving agent of the relations of production of these works. With more than ten years of clear hindsight this now seems obvious. In the later eighties and early nineties other series of works also preoccupied me alongside and sometimes interleaved with the Grease Works. These were the series (1) Mayor of Leipzig/Jacques Louis David Works, (2) Mute Works and (3) Enola Gay Works. All four series of works had a number of works which crossed into one or another, or a number of, the other series. In short, the boundaries between the series of works are porous. The software programmes (either grease, or in the work of the nineties, automated projected image technology and/or conventional computer software programmes) cross series, are often intra-series.

The grease was the initial software programme. The second programme introduced was automated projected image technology projected on to the hardware (tableaux surfaces of various kind - hardboard, canvas, etc.). Some later Grease Works use both kinds of software (grease and automated projected image technology). Mainly these works have remained in the form of the initial drawings.[2] Throughout the nineties the largest body of work was constituted of these kinds of materiel. The first work of the nineties which realized the work past the drawing stage is Work by a Split-Brain Artist, shown at the IMMAGlen Dimplex Prize exhibition at the Irish Museum of Modern Art in 1994. This particular realization is a variation on an initial plan which remains in the form of a series of plans/drawings and notes, which was a characteristic way of working with this body of work. And many of these plans/drawings remain in this form, although should a suitable opportunity arise I would still like to realize them (see note 2). Some of the later works (from around 1995) would, ideally, incorporate a software which continuously develops.[3]

Thus these software entrants (implemented by whatever technology) are attempts to model an artistic agent, an artistic subject. Thus I guess these works may be seen as representations of representers (artists). So, in one way at least, I viewed these works as agents/subjects rather than as objects, keeping in mind the limitations outlined in note 1. Throughout the nineties and early 2000s I maintained a strong preoccupation with such areas as genetic algorithms, automata theory, which I thought, at that time, would entail more direct involvement in computer science/artificial intelligence/cognitive science areas than hitherto. Whilst an interest in cognitive science remains central to my ongoing work, I am now more critical of computer science and artificial intelligence as resources for modelling the mind. I remain though, for example, intrigued with studying some areas of mathematics, although not necessarily to as direct feeds into my practice. Such study, as I have found to my cost, can be very time consuming.

Some points of continuity seem to stay with the practice. A characteristic twinning of painting/software text remains and has been steadfast in the work since 1996. This kind of twinning seems to act as a kind of bridge, in the sense that it is securely tied into a traditional technology (painting), the ontology of which safeguardedly chaperones the work as art. The idea of making work that both hangs in and out of art has interested me a long time. It seems a kind of space where some productive questions might be raised.

Be this as it may, qua painting and drawing, it seems that both slide-projection software and computer software offer some purchase upon the notion of a work-agent which reflects and comments upon itself, including the history of any given genre, technology, set of cognitive resources, etc. These reflexive and iterative possibilities have stayed as preoccupations of my practice. Not the least of the historical aspects which the work may continue to reflect upon, is the status and condition of the avant-garde model of the artistic subject (AGMOAS). The Grease Works mark something of a step along the way of this still ongoing concern in my practice.

Notes.

1. I studied a lot of material from the artificial intelligence (hereafter AI) area in the first five or six years of the nineties. Minsky, the Churchlands, Dennett, for example, as well as some of the foundational texts from the likes of Turing and McCarthy. But I have never been able to do anything but heed the reservations concerning many of the claims coming from the AI constituencies expressed by Noam Chomsky, many aspects of whose work, in respect of my practice, has remained a foundational and persistent influence from the late sixties to the present.

2. There are many of these drawings I would like to realize as objects should the opportunity of space or commission arise (e.g. a suitable exhibition space with appropriate funds/resources to realize them). The reason I have not made them otherwise in my own time and on my own funds is largely a question of storage since I have not for more than ten years worked with a particular dealer on any permanent basis.

3. This notion is one in which I remain interested. I guess it goes back a long way, to at least the permanent preoccupation with text started, at the very latest, in Art & Language in the sixties.